This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Growing up in South Dakota, Morgan never felt pretty enough. As a biracial kid in the mostly white Sioux Falls, she worried about her hair, her nose, her weight. But she didn’t think much about her teeth, which were relatively straight and white. At 13, she got braces to correct a slight overbite, and when they came off, she loved her smile. But in her early 20s, she started comparing her teeth to women’s she saw on Instagram and The Real Housewives, and she began to fixate on minor flaws. Her bottom incisors, she could now see, were too round, and there was a tiny gap forming between them. Despite her braces, her top teeth were slightly crooked.

In 2017, at 22, Morgan moved to Atlanta. She worked for an insurance company during the day and a bar at night, where the other waitresses were gorgeous. They wore shiny weaves and Balenciaga sneakers; on Instagram, they posted photos from their luxury highrise apartments, courtside seats at NBA games, and VIP sections at clubs. A few of them had dental veneers they’d gotten on trips to the Dominican Republic, where the cost of the procedure was low. It seemed like it had been easy.

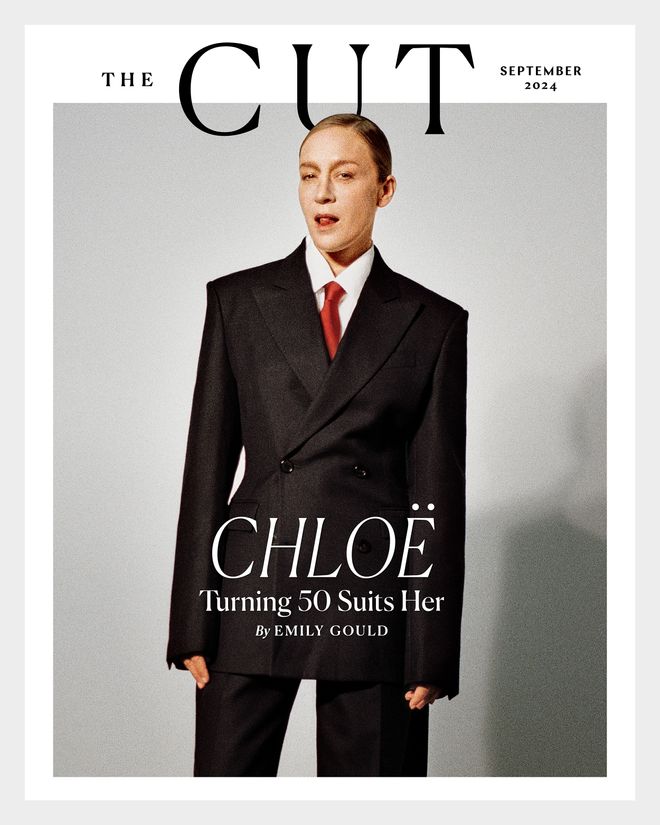

In This Issue

In 2020, Morgan quit the bar and started working remote. She spent hours a day online and significantly more time than usual looking at her own reflection. Morgan had always promised herself that she wouldn’t be like her mother, who obsessed over her own weight without doing anything about it. Instead of sitting around and hating herself, she thought, What can I do to improve myself so that when I get out there again, I’m brand new?

Getting quality porcelain veneers in the U.S. would have cost Morgan somewhere between $20,000 and $50,000. (Some names in this article have been changed and some last names withheld.) But in 2021, after she’d moved back home to South Dakota, she found a dentist in Colombia who offered the procedure for $8,000. His work, posted on Instagram, looked natural. She saved up the money and flew to Medellín. The majority of veneers are installed after a person’s natural teeth have been sanded down, but the practice in Colombia claimed to offer “no-prep veneers.” Morgan thought her teeth would remain intact under new ceramic covers, but her appointment began with a dental assistant shaving down her enamel with a drill and bur. She was immediately in pain and started to panic, but she didn’t speak enough Spanish to communicate properly. “I just sat back and prayed to God that it would be okay,” she told me, her voice catching. “I thought, Look at the situation you’ve put yourself in right now.”

Twelve hours later, the dentist sent Morgan away with shaved-down teeth and without the standard temporary covers to protect them. She was not consulted about the color or shape of the veneers now being made in the lab. For the two days she waited in a nearby hotel, it felt strange to eat; her enamel was so thin. Morgan scrolled through the beautiful “after” pictures on her dentist’s Instagram page for reassurance. This is what I’m doing it for, she told herself. I’m gonna love it at the end.

When her permanent veneers were finally applied, they were oversize and blindingly white. Within hours, a new pain began — a heavy pulling, like a dumbbell weighing on the raw remnants of her teeth. Back in South Dakota, she started taking Advil each day. Her bite was now misaligned, and when she ate, she bit her cheek. She couldn’t afford the tens of thousands of dollars it would cost to replace them, and she also couldn’t just get them removed: Her teeth beneath the shells were destroyed. She stayed in bed for weeks, feeling suicidal and praying: God, if you let me wake up tomorrow and have my own teeth, I promise I’ll never hate myself.

The word veneer implies a surface-level intervention, an exterior casing, like a slipcover on a worn chair. But dental veneers are invasive medical prosthetics, and in many cases they alter patients’ teeth drastically and permanently. The most common form are porcelain veneers, which typically need to be glued onto a rough surface, created by shaving off a layer of the patients’ teeth. There is no dental procedure that can replace the lost enamel. Composite veneers, which allow for a resin to be applied directly onto teeth, can in theory avoid this damage, so long as there are no complications. In the very best cases, porcelain veneers need to be replaced every 15 to 20 years; composites last roughly half as long. But veneers done poorly are a different story altogether: They can lead to major and irreparable health consequences, including rotting teeth, gum infections and disease, TMJ disorders, and other chronic conditions, including unresolvable pain and degradation of the jawbone.

Twenty years ago, these risks didn’t matter much for most people. Veneers were reserved for entertainment-industry stars, particularly actors; the very rich; and patients with significant dental problems. Today, these fake teeth are everywhere, especially online, and the market for the prosthetics has more than tripled, according to the dentists I spoke with, and is expected to grow by more than 70 percent by 2030. Dentists told me, this growth has been driven in good part by people in their late teens to mid-30s who do not have any obvious dental defects. These patients are often looking to make minor tweaks: to whiten, to change the shape of a single canine, or to fill a small gap. Jason Olitsky, a Florida-based cosmetic dentist who regularly sees clients in their mid-20s, told me, “Patients come to our practice with smiles that are B’s or B-pluses, and they want them to be A-pluses.” Sara Hahn, a California-based prosthodontist — a specialist in complex dental restoration — told me that when she opened her practice in 2014, most of her veneers patients needed to cover chipped or decayed teeth and had been referred to her by other dentists. But since the start of the pandemic, she has seen a threefold increase in patients who find her independently, often through the viral #VeneerChecks she does on her TikTok page, dissecting celebrities’ cosmetic work. These new patients want to know, she said, “‘What should I do to change my smile?,’ as opposed to ‘How do I fix this one problem that I have?’”

Many practitioners like Hahn are careful to communicate the risks of veneers, especially to young patients. Hahn tells them, “The tooth is a finite object. The more things you do to it, the chances are higher that the nerve on the inside is going to die or the gum will shrink away.” And examples of shoddy and completely botched veneer work can be found all over the same platforms where influencers show off their synthetic teeth. Still, dentists in the field say that many patients who get veneers do not understand the gamble they’re making. “When it goes wrong,” said Hahn, “it’s devastating.”

One irony is that many of these younger patients aren’t just risking these side effects on perfectly healthy teeth; they’re asking for veneers that look increasingly like subtly better versions of the teeth they already have. Veneers started as a Hollywood invention. In the late 1920s, makeup departments brought in dentists to make temporary teeth out of acrylic and denture powder. These early veneers covered over spaces between Judy Garland’s front teeth, masked James Dean’s missing front teeth, disguised Joan Crawford’s root decay, and allowed Shirley Temple productions to carry on without audiences knowing that the actress had lost her baby teeth.

Over the following decades, dentists developed longer-lasting veneers — these required etching into the tooth’s surface — and by the ’80s, most were made to be permanent. The artificial teeth of celebrities like George Clooney, Tom Cruise, and Demi Moore heavily influenced the public’s conception of the ideal smile. And by the aughts, oversize teeth, white as a camera flash, suited the broader popular aesthetic of exaggerated perfection: larger breasts, smaller waists, and deeper fake tans. Jon Marashi, an L.A.-based dentist whose clients include Halsey, Ben Affleck, and Kate Hudson — his Instagram bio is a quote from Cher, who calls him the “Tom Ford of Cosmetic Dentistry” — noted that large white veneers appeared on the red carpet “at that exact moment that you saw people wearing True Religion bell-bottom jeans. The flare couldn’t be big enough, and the pocket flaps could not have been more ornate.”

These ostentatious teeth — “obscene,” said Marashi — were also the result of too much demand. As veneers became more popular, Marashi continued, there weren’t enough skilled dentists and ceramicists to keep up, and people without the proper training began to fill the gap in the market. The results were often bulky and clumsy.

It was around this time that veneers first reached mainstream consciousness. The marketing successes of Invisalign and Crest Whitestrips drew attention to teeth as a cosmetic concern, and reality shows like The Swan and Extreme Makeover exposed viewers to dramatic dental transformations. Instagram and then COVID supercharged demand. Dr. Michael Kosdon, the New York–based specialist who made Hilary Duff’s current set of veneers (the ones that replaced previous sets tabloids and blogs dragged for being too horsey), told me, “The pandemic and Instagram are the best things that have happened to cosmetic dentistry. I had my best, busiest two years then because everyone was home on Zoom calls, looking at their smile on their monitors all day.”

Those who got veneers in that era often fell victim to the gravitational force of Instagram face. Troy Jensen, who worked as Kim Kardashian’s makeup artist from 2008 to 2010, described the look: “Jawlines are just a little too squared off, the lips are a little too big, and the teeth are too white and Chiclet-looking.” Blocky veneers became ubiquitous on reality TV, especially on dating shows like Love Island, where contestants were said to have “Turkey teeth” — shells from cheap procedures in Eastern Europe.

The problem with getting fashionable teeth is trends can change. In the past few years, the “more is more” aesthetic has crested. Now it’s the Hollywood actors who have left their teeth alone who have a special charismatic pull: Zendaya has slightly maloccluded incisors; Ayo Edebiri, a noticeable overbite; Sydney Sweeney and Timothée Chalamet have prominent gumlines; and Jacob Elordi and Léa Seydoux have gap-toothed smiles. You can still find blocky and blinding veneers on young celebrities — JoJo Siwa, Selena Gomez, and Miley Cyrus, to name just a few — but the rich and famous are now just as likely to opt for subtle adjustments. Marashi told me, “I’ve kind of turned into a beauty consultant to a degree. There’s not a working actor on the planet that doesn’t have an industry colleague who has a set of big white chompers. And they’re like, ‘I don’t want to end up like that.’” Top-tier cosmetic dentists are also fielding more requests from A-listers to tone down their megawatt smiles: Kosdon was enlisted a few years ago to fix Kim Basinger’s old veneers, which he said had looked “plasticky.”

Marashi said the young non-famous patients who now turn up at his office will often show him older pictures of their own teeth. They want realistic casings with slight flaws replicating the translucency and misalignments — stealth veneers, bespoke to fit a person’s face. Many of these new young customers approach the procedure as if it were a much lower-stakes cosmetic treatment, like a shot of Botox. “It’s almost like a filter on Instagram,” said Alison Fishman, a prosthodontist in San Mateo, California. “People think, You can just snap your fingers and give me a beautiful smile.” Some are getting veneers for special occasions like weddings, others for job interviews. “I hear that a lot,” Kosdon told me. “It just gives you more confidence when you walk in a room.”

But it’s not easy for the average person to get subtle or even well-made veneers. “I will be the first to say that there is a red rope for getting this,” Marashi said. Celebrities have access to exceptional cosmetic dentists who offer minimally invasive composite-resin treatments painted onto teeth with extreme precision and who enlist expert ceramicists to craft porcelain covers that mimic the fine textures of real teeth. “You really have to be an artist,” said Jordan Davis, a Utah-based cosmetic dentist. “For the average dentist, it’s a little over their heads.” Olitsky told me, “I’m only as good as my ceramicist. I can do everything right, choose the wrong ceramicist, and not get a good result.” Such skilled craftspeople are few and work with only the best dentists. Davis charges on the low end for top-tier veneers: $20,000 for a set of ten. Many of his colleagues on the coasts, such as Marashi, charge more than twice that amount.

For regular people seeking veneers, there’s a vast marketplace of nonspecialist dentists, overseas practices, and “veneer techs” — a growing industry of non-dentists who falsely claim to be certified in the procedure. Some of these bargain-priced practices do not or cannot deliver quality work.

In 2022, 27-year-old Miranda Rae, from New Jersey, discovered she could get discounted veneers at a practice in Miami. Her usual dentist had quoted a price of $17,000; the office in Florida would charge less than half that. Rae had always been insecure about her upper-right canine, which was so small it left a gap when she smiled, and she wanted whiter teeth. In Miami, her temporary veneers matched her face perfectly, but when she went back for the permanent set a few days later, and the dentist attached it with what he said was a bit of temporary glue to test the results, the front two shells were cartoonishly long. The doctor tried unsuccessfully to remove them and eventually trimmed them back with a drill, leaving a sharp, square edge. The practice had a satisfaction guarantee, offering fixes for patients who returned within 30 days, and in the Uber back to her hotel, Rae tried to reach the staff to schedule a follow-up. No one responded until she posted a comment under one of the office’s recent Instagram posts, but she still couldn’t get an appointment. Rae boarded her flight home the next afternoon. When she got back to New Jersey, her gums were inflamed and bleeding. She noticed her bite had changed. The practice finally scheduled a follow-up after she threatened legal action in an email. But when Rae returned for the new appointment, six months later, the office said she was not on the schedule. She was sent to another location, where a dentist took a few minutes to sand down her incisors and then told her to come back another time. The practice refused to refund Rae for her veneers. She approached seven different lawyers in an attempt to file a suit against the company, but no one was willing to take on the case. She eventually gave up.

Jade, who lives in Los Angeles, was 20 when a dentist told her she needed composite veneers. She didn’t question the advice — she’d been grinding her teeth so much it was painful to eat and drink — but the procedure would cost $1,200 per tooth, an amount she couldn’t afford. She decided to drive to Tijuana to get the work done for $2,500 total. The dentist began by trimming her gums with a laser, which she found strange, but he told her this was standard practice and that they would grow back. Though she came away with veneers that were a little bulky, Jade was happy: Her tooth sensitivity was gone. But a few months later, her gums began to swell and her mouth was throbbing with pain. The veneers were rubbing up against her new, still-raw gumline, and food was getting stuck between the injured flesh and resin casings. Jade returned to Tijuana, where the dentist told her that her gums were infected and that he would remove the affected portions, cutting away small inflamed flaps of tissue that were now covering the tops of her teeth. She returned roughly ten times within a few months, as the dentist sliced out more of her gum tissue. The pain persisted, and her breath became terrible. Her fiancé and her 3-year-old daughter refused to kiss her.

After a year of suffering, Jade was diagnosed with periodontitis, an infection that can destroy the bones supporting a person’s teeth. She has now had most of her veneers removed, but the damage is irreversible and will likely get worse. “The roots of my teeth are starting to show now,” Jade said. “I’m having bone loss. My jawline is completely depleted.” She doesn’t smile anymore and tries to cover her upper teeth while talking; her composites were shaved off, leaving white patches.

Dominique Watson, from Memphis, got porcelain veneers at 35, in 2021, from a dentist with a large Instagram following. She heard he had a reputation of high-quality work and wanted to support a Black-owned business. She thought the veneers were gorgeous, but less than a week after the procedure, one of the hard shells fell out into a plate of scrambled eggs. Her dentist readhered the veneer. A few days later, it fell out again. About a week after that, while she was brushing her teeth, a second veneer came out. Another came loose that afternoon in the middle of her shift selling jewelry at a pop-up shop. That night, at a Mexican restaurant, yet another fell out as she bit into her food.

Over the next three years, she said a veneer has detached at least 25 times — ruining family birthdays and vacations and transforming meals into nightmarish, paranoid trials. She accidentally swallowed veneers on two separate occasions. Watson became introverted and started taking antidepressants. She and her partner ended up separating. “We used to go out every weekend,” she told me. “But I wasn’t that upbeat, high-spirited Dominique anymore.” Because of the cost of replacing veneers, Watson had the shells repaired one by one as they came loose; dentists said her teeth had likely been improperly prepped or that her veneers had been attached with low-quality adhesive. In 2022, she tried to sue her dentist, but the case was dismissed. In August 2023, she sent a formal complaint to the Tennessee Department of Health. It’s been six months since any of her veneers have fallen out, but Watson described herself as living in fear. “I did something nice for myself,” she said, “and in turn, it caused me so much psychological trauma.”

Multiple cosmetic dentists have told me that their revision work on veneers — both fixing ugly casings and managing truly mangled jobs — has doubled. Marashi said that he now spends half his time on edits and repairs.

Some specialists still don’t see any harm in young people getting veneers. “Why get a fast car when you’re 60?” Kosdon said. “Enjoy it when you’re young.” But others have begun actively dissuading younger clients from the procedure no matter who is doing the work. Hahn, the California prosthodontist, encourages patients to try interventions with drastically fewer downsides, including bleaching, braces, and Invisalign. She now turns away younger people who have found her through social media: “I say, ‘Someone will take your money. But that’s not going to be me.’”

In late July, I decided to sample veneer consultations to test what patients are actually being told about the dangers. In the office of Dr. Tandeep Malhotra, in a Tribeca high-rise, I was offered a “comfort menu,” from which I could select small luxuries including hydrating eye patches. Malhotra, with a block of thick black hair and a suave demeanor, handed me a plastic mirror and asked me to describe what I didn’t like about my smile. Malhotra has 14 years of experience in veneers and charges around $2,500 per tooth, or $60,000 for a complete set. This was the white-glove experience.

Leaning back in the exam-room chair, I pointed to wear on my front two incisors from grinding and a crooked tooth on the bottom right. Some of my canines were sharp. He scribbled on a notepad as I went on: I had yellow staining and, in some places, noticeable white spots. “When you smile, does it bother you?” he asked. “Are you always sad?” It’s not that dramatic, I said, but since working on this story, little imperfections I’d never noticed had become glaring.

If I were to proceed with Malhotra, X-rays would be taken to check for structural problems, such as bone loss, cavities, or unhealthy gums. “You can’t build a skyscraper on sand,” he told me. Then, based on digital scans and photos, he’d design a mock-up set of veneers with his ceramicist; the shells would be constructed in wax, and we would scrutinize them together. I was careful not to prompt Malhotra to lay out the risks, and he did not mention the more harrowing possibilities I had come across in my reporting, but he did emphasize the treatment’s permanence. “If you want to do it, you’re going to be fully committed,” he said. “This is not reversible. Once the enamel is shaved, it’s not coming back.”

A few days later, I scheduled a video consultation with Dr. April Patterson, who runs Dr. Patty’s Dental Boutique & Spa in Fort Lauderdale, to sample a more affordable service. On realself.com, where customers review cosmetic procedures, the feedback was mostly positive and some patients raved about the practice, which offered Botox shots and something called a “Vampire Face-lift.” Posts on Yelp were more negative and included a series of furious one-star reviews. One woman wrote that her veneers procedure was “the most traumatic experience of my life. I am still in pain every day from what they did to me.” (Patterson’s office wrote back that that the patient was “dismissed from the practice for behavioral issues” before the final veneers were cemented.)

Patterson offers four tiers of veneers, ranging from what she called the porcelain “Bentley,” which costs up to $2,200 per tooth, to the “Subaru,” 3-D-printed composites for $600 each. After a few minutes of questions, she told me I was a good candidate for veneers and recommended the Bentley. As a writer, I would be in the public eye, she said — why wouldn’t I take the opportunity to look my best? Besides, she noted, not incorrectly, that I was “no spring chicken.” She also suggested I get Botox in my jaw muscles; it would help with my teeth grinding and, as a “cherry on top,” my face would look slimmer.

She brought out some color samples, suggesting a shade close to “the whitest white.” People usually don’t like yellow tones for their permanent veneers, she said. If I were to become her patient, I would choose the color and shape, and she’d do the rest. “I tell most clients, ‘Don’t get too involved in the process,’” she said. “This is my art. I’m the queen of veneers.” Unless I paid extra, I wouldn’t get to try out a custom prototype before giving feedback on the permanent set. “I’ve been doing this too long,” she said. “I know what I’m doing.”

Patterson didn’t mention any of the risks or discuss the prosthetics’ permanence, so at the end of the call, I asked her if there were any dangers. While she said the procedure “can be very risky,” especially if a person’s teeth aren’t properly prepared, with experts like herself, the risk is “very, very low.” When I asked about some of her subpar Yelp reviews, she answered that people who post on the platform tend to be “bullies.” She won’t stand for anyone disrespecting her staff: “Me? I will get right back at them.” In one posted reply to a former patient — who claimed she spent $40,000 on faulty veneers at Patty’s — Patterson called her “the nastiest individual I believe I’ve ever come across.”

I had hoped to speak to the dentist in Medellín who installed Morgan’s shoddy veneers. He would not agree to an interview, though his staff sent an email response denying some but not all of Morgan’s claims. The office in Miami that failed to fulfill its guarantee in Miranda Rae’s case also would not speak to me. Same for the Tijuana clinic that cut away Jade’s gums. But I was able to get in touch with Anthony Price, the Memphis dentist who had performed Dominique Watson’s procedure.

In a video consultation, Price, who wore a lab coat and scrub cap, was friendly and professional and suggested the most conservative approach of any of the dentists I’d spoken with, recommending that I get braces for six months prior to veneers; this would minimize the amount of enamel that a dentist would need to cut away from teeth that were currently crooked. “Once you shave your teeth down, it’s definitely permanent,” he said. “It’s something you can’t come back from.”

I asked Price if patients were ever unhappy with their results or if veneers ever fall out. “This is an art and a science,” he said. “We’re changing what God gave us. But we strive to do the best. We use the best materials; we do the training that needs to be done. And, you know, sometimes things can go wrong.” When I asked specifically about the possibility of multiple teeth falling out, he said, “I’ve seen everything go wrong. I’ve done so many thousands of cases, so, of course, I’ve seen that. We know how to correct it.” In those cases, he told me, it’s often because the patient is doing “something crazy,” like grinding their teeth at night, biting into chicken bones, or chewing on their fingernails. When I called Price again a few days later to ask about Watson’s experience, he said that she had brought a suit against him, which was dismissed.

A few weeks after her disaster in Colombia, Morgan found Olitsky, the Florida-based dentist, online. She told him her story, and his office cut her a deal: Let them share her experience in an Instagram post about the dangers of dental tourism, and they would give her new veneers for just $12,000. She didn’t have the money but immediately said “yes” and gave them her credit-card number. Over two trips, Olitsky drilled off and replaced each veneer. When he was done, Morgan’s pain was gone and her bite felt normal. But the saga was not really over and still isn’t. Morgan’s new veneers are much more subtle, but they aren’t her natural teeth. “I just miss the old me,” she said. “Her smile was so beautiful. She was perfect.” Watching Dune: Part Two this summer, she was fixated on Zendaya and Timothée Chalamet’s mouths. The flaws of their real teeth were part of their appeal. “I envy them so much,” she said. “I would trade anything in this world to go back.” She has never told her boyfriend about the trip to Colombia or the botched veneers. She can’t really think about any of it without crying. She’s $10,000 in debt, and she tries not to smile.

ANSWERS

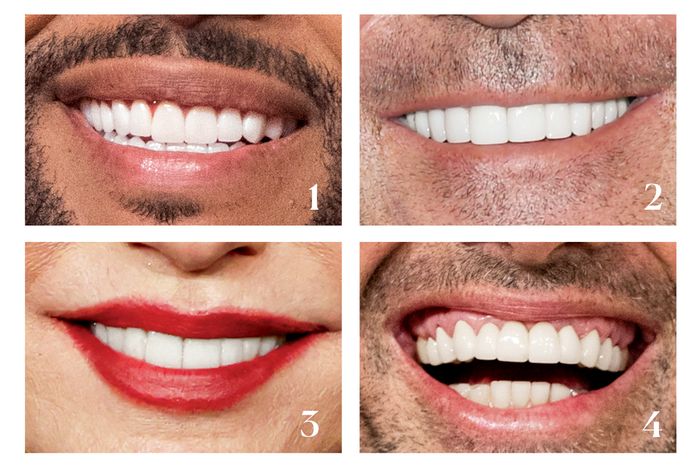

Whose horse teeth are these? 1. Faye Dunaway 2. Miley Cyrus 3. JoJo Siwa 4. Jürgen Klopp

Whose chiclets are these? 1. The Weeknd 2. Simon Cowell 3. Shania Twain 4. Walton Goggins

More From The Fall Fashion Issue

- Behold Your Fall 2024 Horoscopes

- The 8 People You Meet at Every Fashion Week Party

- Usher’s Art of Seduction