Editor’s note: This story is part of a New York Magazine exploration of the ethics of pet ownership, sharing a variety of points of view on whether we’re equipped to care for the animals in our homes. The magazine confirmed the welfare of the cat prior to publication.

Summer in New York, sunny Thursday in the park. A ponytailed woman in the realm of 30 years old gazes into the middle distance. At her breast is a baby. Tied sloppily around one of her ankles is a leash, and connected to the leash is a glossy auburn dog standing a few feet away, morosely examining a piece of trash. When the dog gets bored with the trash, he trots back to his owner and begins to tentatively hump her leg. Alert to any change of movement, the baby detaches from her mother with a squirm and a wail. The dog quickens his hip thrusts into exuberant plunges — until the owner stares daggers down and says, loudly and clearly into the judgmental Brooklyn air, “Fuck off.”

And off he fucked, that little dog. I wouldn’t have noticed any of this except that I was sitting at the next bench over with my own baby, and I too became enraged at this dog whose humping had triggered a multi-organism chain reaction that ended in my own child bursting from tranquil sleep to fussy consciousness. A year ago, I would have been startled by the woman’s vitriol as well as my own. But now it made sense. If I ponder the possibility of being humped — by anything — while engaged in the delicate process of nursing a baby, I think to myself, That way lies a psychotic episode.

In This Issue

Birthing a child is an efficient way to shatter certain delusions while fostering a set of brand-new ones, and pets seem to suffer from this shift. I don’t know many pet-having persons for whom the introduction of a baby didn’t cause a plummeting of interest in the legacy mammal. In some cases, this disillusionment is temporary, in others permanent. Cats, being standoffish in nature, tend to be grievously neglected; dogs, having nonnegotiable daily needs, are more often resented. The cost of a pet can become a special locus of bitterness. One parent, Audrey (not her real name; everyone in this story was granted a pseudonym), determined that “$10,000 is the absolute upper limit of how much I would spend to save the dog’s life, whereas my previous answer would have been ‘infinity.’ ” “It’s so bad,” Camilla, who has two children, told me. “The dog needed surgery on her leg at the beginning of June, and I asked the vet if I could put her down instead. He looked at me like I was a monster. I shelled out $5,000 we don’t have on the fucking dog instead of the millions of other things we needed it for.”

A few months ago, my friend Heidi was walking her dog down the street. “The baby would have been, like, 6 months old. The dog was pulling and barking and being annoying in general,” she told me. “And I very audibly said, ‘I wish you would die.’ ”

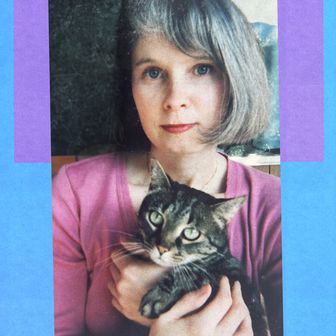

I got my own cat, Lucky, ten years ago. It was an act of selfishness. I was a lonely 24-year-old who craved on-demand love from an adorable creature. It was clear to friends and family that Lucky, like most or all cats, was only intermittently tolerant of me, much less loving. But my brain was a capable converter of her routine activities into evidence of affection. It didn’t bother me when Lucky shredded the furniture to smithereens since it was all secondhand Ikea stuff anyway — a mere step up from garbage. She slept on my pillow every night. I combed her for hours every week with a miniature kitty comb. I purchased bottles of sustainably harvested fish oil because it promised to prevent heart disease or something. On cold days, Lucky napped on a tartan cashmere blanket beside a space heater set up for her at the foot of the table where I worked. All of my disposable income went toward fancy cat food and wholesome toys. The cat arrived, in other words, during a period when I was not thinking of the future, which is the whole point of your 20s.

Nonetheless, the future occurred. When I got married at 30, Lucky took an active and territorial dislike to my husband. It was unpleasant but manageable for everyone. A few years later, we had a baby, and my postpartum loathing of Lucky made me wonder whether I might be a late-onset psychopath. In the months following the baby’s arrival, any redirection of attention sparked fury. If Lucky nuzzled me as I nursed in bed, I shoved her away. When she barfed on a nursing bra, I threw the soiled garment at her head (and missed). When she threaded through my legs in figure eights during diaper changes, I could barely suppress the urge to — not kick but firmly scoot her away with a foot. (I didn’t, I didn’t.)

Basic needs went unmet. I often forgot to feed Lucky, which caused her to eat houseplants in desperation and puke them up. She shat and urinated on the floor in protest of her overflowing litter box. A few weeks in, I abandoned the effort of wet food altogether and placed a trough of dry food in a corner; Lucky binged and gained a statistically significant amount of weight, which made it impossible for her to self-groom, leaving her greasy and coated in dandruff. She lost at least one tooth. (No idea where it went.) I forgot to fill her water bowl, which I didn’t realize until I saw paw prints all over the toilet seat — her hydration source of last resort. The toilet paw prints broke my heart a little bit. If I treated a human the way I treated my cat, I would be in prison for years.

Eventually, Lucky gave up and became depressed. Her movements changed. She skulked around the baby, slept in a sad cowering position, hesitated before approaching her food, eyed me with an uninterpretable but distinctly negative affect. These observations about her condition coexisted with an unwillingness on my part to change anything about it. By the time the baby was 2 months old, I hated Lucky so much I began to leave our windows open in the vague hope that she would take the initiative and leap out of one — not directly to her death (we live on the ground floor, so a level of plausible deniability factored into my calculations) but, realistically, to her death. Call it voluntary catslaughter.

-

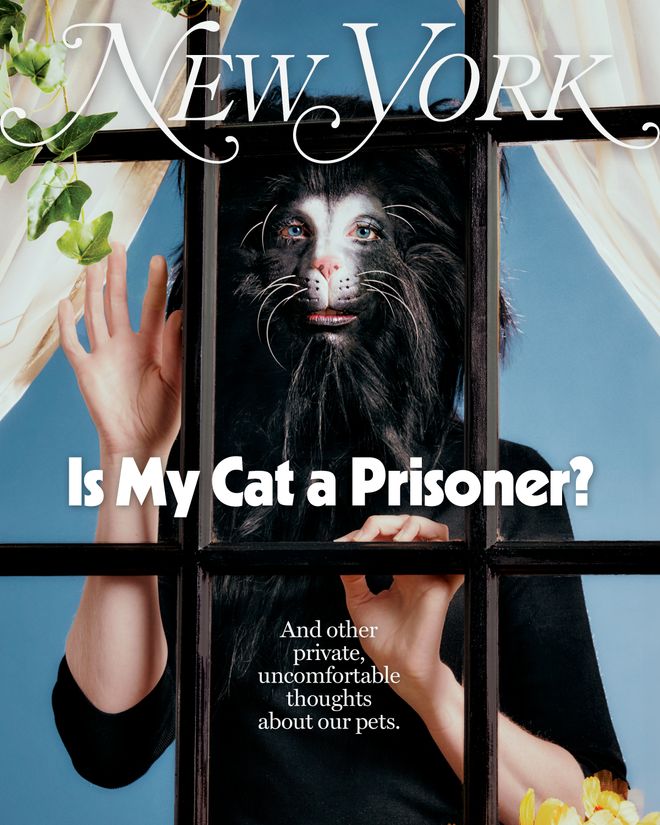

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior? -

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

-

Is My Cat a Prisoner?

Is My Cat a Prisoner? -

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free? -

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment?

Is My Dog Too Big for My Apartment? -

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?

How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug? -

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets? -

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

Am I a Terrible Pet Parent? -

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think.

Are Emotional Support Animals Legit? What Vets Really Think. -

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl? -

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior? -

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

Looking back, I realize our dog was like a ‘practice baby,’” said Cynthia, now a mother of three. She took the dog to work with her; her husband cuddled him after she went to sleep. Before giving birth to a daughter, Laurel told me, she and her partner “poured all our dormant parent energy into the dog.” They bought doggy outfits, took the pup on vacations, photographed her daily. Then the baby came — the real baby. No more hourlong walks and photo shoots. Instead of curling up next to Laurel on the couch, the dog lurked at the opposite side of the room. “I felt like I’d dissolved a four-year relationship,” Laurel said.

Like me, none of the women I spoke with had intentionally obtained her pet to use the animal as training wheels for a baby. None would think of seeing her pet in such frostily instrumental terms. They got their pets for all the usual sweet reasons: for companionship, to offer a safe home to a rescue, because they’d grown up with pets. Just because a pet can function as a prototype baby doesn’t mean it must — or that it is only that.

But let’s grant that it happens. You had a pet who was your baby, and now you have a baby who is your baby. Does that mean the pet is sentenced to irrelevance?

The answer from most of my polling group was “Yes, but it’s not a life sentence.” More like one to five years with time off for good behavior. The common thread among their experiences was this: Parenthood inevitably alters a pet’s position in the household, but the degree to which it does needn’t be morally egregious. You may accept that your pet is no longer the primary recipient of love and resources while still according it the status of a cherished being. Wait it out, they implored me. “Don’t trust your feelings right now,” said Cynthia. She promised my affection for Lucky would return once the baby started noticing and interacting with her.

At 3 months old, my baby was of roughly equal size with my cat. Three months is when babies start tracking their environment — looking around, perceiving entities that do not have a nipple. It was around this time that I found myself perched on the bed one night trying to interest the baby in a dragon-shaped toy. The toy was new, a recently unwrapped gift from my sister. When the dragon was waggled, a bell sewn into its belly made a jingling sound. The baby didn’t care for the dragon, but Lucky careered to the bed as soon as the toy’s inner bell was activated. The jingling was similar to the sound my fingernails made when I drummed them against the radiator pipe near Lucky’s food bowl — the signal that dinner was served.

Having jumped onto the bed under false pretenses, Lucky froze. Her overgrown nails dug into the duvet cover. She stared at the dragon, the baby, me. Then back at the baby, who wobbled his head in the cat’s direction. Lucky moved closer. For six or seven seconds, the two creatures stared at each other. A hint of the affection Cynthia predicted flared up in my chest. As did a flicker of irritation because now the cat had to be fed or watered or whatever.

Then I remembered something that Natasha, a mother of two kids and one dog, had told me: “Being irritable and not having enough love are two different things.” At that moment, on the bed, both happened to be true — I did not have enough love for the cat, and I was irritable. But that didn’t mean one followed from the other. In fact, a mountain of evidence pointed to the opposite: Every person and animal I’d ever loved had caused me vexation, and I knew myself to be a periodic or chronic irritant in the lives of my entire family, all my friends, my partner, and my colleagues — yet none of them ever invited me to self-destruct. I haven’t fallen back in love with Lucky, but it could still happen. I’ll shut the windows until then.

Is My Cat a Prisoner? And other ethical questions about pets like …

➭ Are We Forcing Our Pets to Live Too Long?

➭ Am I a Terrible Pet Parent?

➭ What Do Vets Really Think About Us and Our Pets?

➭ I Am Not My Animal’s Owner. So What Am I?

➭ Was I Capable of Killing My Cat for Bad Behavior?

➭ Should I Give My Terrier ‘Experiences’?

➭ Is There Such a Thing As a Good Fishbowl?

➭ Do Runaway Dogs Deserve to Be Free?

➭ Are We Lying to Ourselves About Emotional-Support Animals?

➭ Does My Dog Hate Bushwick?

➭ How Agonizing Is It to Be a Pug?