Inside the sold-out Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis on Saturday afternoon, the crowd had started to boo. WNBA rookies Caitlin Clark and Angel Reese were facing off for the first time in their pro careers, and it had been a close, physical game. From the press overspill section, which had been set up to accommodate the more than double the usual number of members of the media present, Indiana Fever president Allison Barber and I looked up at the JumboTron to see what the fuss was about. Barber had been mid-sentence, telling me about her “three C” strategy for franchise growth —“commit, compete, and contribute” — when suddenly, with 15 seconds left in the third quarter, the Chicago Sky’s Chennedy Carter had body-checked Indiana’s No. 1 draft pick to the floor before the ball was even in play.

Watching the replay, I thought it looked like a hard foul, but also not much more than the kind of “welcome to the big leagues” greeting that WNBA legend Diana Taurasi suggested Clark might get as a pro back in April, when Clark’s Iowa Hawkeyes were still rolling through the NCAA tournament. (Even Clark, interviewed courtside moments after the shove, felt the same way: “It’s just not a basketball play, but you gotta play through it,” she said. “That’s what basketball is about at this level.” The league later upgraded the foul to a flagrant.) Barber, for her part, could only raise her eyebrows when I asked if she had any comment, and we watched as the franchise’s prize investment made a free throw and the quarter ended.

The game, and the crowd, moved on quickly. There was nothing to indicate that a firestorm was coming. Within a couple of minutes, the arena was laughing uproariously at an “Edge of Seventeen” sing-along gag on the JumboTron, and the Fever went on to win 71–70, their first home victory of the Clark era. But in the days since, the controversy has nearly swallowed sports media whole as commentators who’ve never really tuned into the league before this season have rushed to weigh in on whether or not Clark is being “targeted” by her opponents with physical play, and offered bumbling racial analysis on the WNBA at large: Carter is Black, and Clark is, of course, the game’s latest great white hope, and the foul has been cast by many as a resentful act of jealousy for the latter’s outsize treatment and sponsorship deals.

Welcome to the WNBA’s growth-spurt season. The league has never enjoyed an audience like this before, for better or worse. Nothing could have prepared longtime fans for sold-out crowds and shattered broadcast records … or the particularly harrowing experience of bros weighing in on league pay structures and team histories that they learned about three weeks ago. But by Monday afternoon, that’s where we were. On First Take, Stephen A. Smith offered his own ham-fisted critique and then glitched into speechlessness when longtime WNBA commentator Monica McNutt pointed out that his program didn’t seem to care quite this much about the league a few years ago. (Smith doubled down, calling McNutt’s comments “highly offensive” and “factually incorrect.) And Pat McAfee, who has been a courtside fixture at Fever games this season, had for some reason called Clark a “white bitch from Indiana” on live television. (McAfee apologized within a few hours.) By Wednesday, Sky security was intervening outside a D.C. hotel when a man tried to confront Carter. “Didn’t realize that when we said ‘grow the game’ that would be interpreted as harassing players at hotels,” Sky forward Brianna Turner, a six-year veteran, posted to X about the frightening incident.

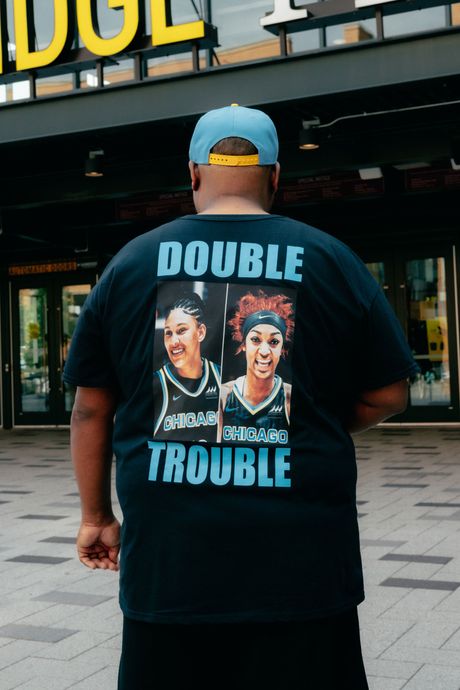

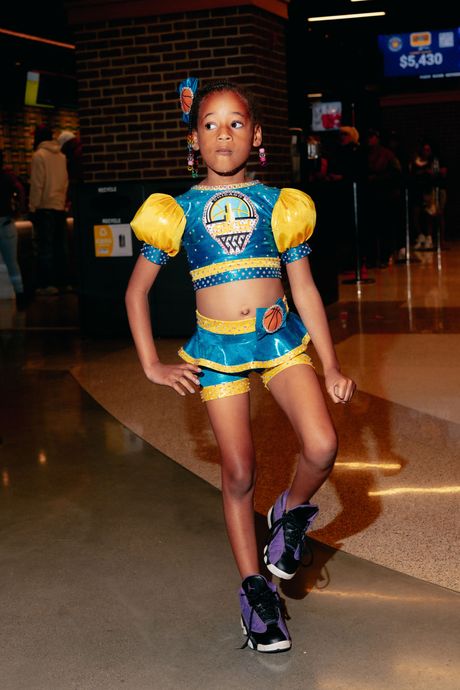

As charged as the discourse off the court has been, the dominant vibe at Indiana games thus far has been one of almost wide-eyed, harmless neutrality. At Gainbridge, the fan who got the biggest cheer on the JumboTron throughout the day was a woman dancing in a radically impartial custom T-shirt: It had a collage of Clark alongside her college foes and Sky opponents Angel Reese and Kamilla Cardoso, framed by the airbrushed title Basketball Queens. Tanya Wood, who’d spent an estimated $700 to travel from Des Moines with her partner, Kim, for their first-ever WNBA game, told me, “Win or lose, as long as Clark has a good game, then we’re happy.” At halftime, I spoke to a boyfriend who was wearing a shirt that read “Watch More Women’s Sports” he’d gotten off of Amazon. “If they had a jersey that had a full roster of both teams,” he told me, “I probably would’ve bought that.”

The growth has been so rapid — in just their first five home games this season, the Fever has already surpassed its total attendance for the entire 2023 season — that the new additions to the fan base, including many men in sports media, seemingly haven’t sorted out how they feel just yet. Even at Indiana’s sold-out game in Los Angeles last month, I watched in bewilderment as the hometown crowd (which has a pair of star rookies of its own in Cameron Brink and Rickea Jackson) tried to decide whether they were rooting for a Sparks win or for Clark to pull up for one of her trademark logo threes on every Fever possession.

And all this for a team that, at 2 and 9, now has the second-worst record in the league. “The Fever’s won just one game,” Dan Lorenzo, who’d made the drive from the Chicago suburbs with his wife and young daughter for the latter’s birthday, told me just before Saturday’s game started. Not too far from where we were standing, there was a roped line overseen by an arena employee just to get into the team store. “But it’s like they won the championship,” he added.

Even if the phrase has already been as overworked as the Fever’s backcourt this season, the so-called “Clark Effect” is immediately clear on game days in downtown Indianapolis. Fever season-ticket sales have more than doubled, according to Barber. There are lines of idling cars to get in and out of the parking garages, and also, notably, there is more than one parking garage in use. (Barber remembers promising her parents early in her tenure that “someday we’ll have traffic. And now we have traffic. It’s awesome.”) I spoke to fans who had traveled from as far as Connecticut, Florida, Tennessee, and, of course, Iowa, many of them for their first-ever WNBA game. The overall impact, Joel Reitz, the owner of a nearby Irish pub called O’Reilly’s, told me, is “like adding another sports team” in Indy. (The Fever, which won a championship in 2012, is celebrating its 25th season this year.)

“It’s been like this since the season started,” a weary arena employee told me as he arranged special Pride T-shirts and koozies at a display table, putting them down almost as quickly as they were snatched up. “It’s like a Pacers game.” A season-ticket holder named Arlana Wood sidled up to ask if they had any of the league-branded Commissioner’s Cup balls in stock. (They didn’t.) Wood has had season tickets for the Fever for every season the team has existed, and over the years she has seen the crowds wax and wane. “I didn’t dread coming, but it wasn’t as exciting,” Wood said. This year, she has loved seeing the look on new fans’ faces when they come to their first game and catch the bug. “It’s like seeing the sunset for the first time, or a sunrise out on the ocean, or a newborn baby,” she said. “They just have a sparkle.”

If it all sounds a bit too wholesome, that’s because in the stands, away from all the noise, it usually is. I half-expected the Clark-partial Indy crowd to greet Reese like an old rival, but the most I saw from my seat was some mild booing during a pair of free throws in the second quarter. (Reese, ever the gamer, waved them off as she hit one of two and hustled back down the court, and she was later fined for bailing on the press conference after the game.) I found Ro-Anne Thomas, the woman who’d been on the JumboTron in the Basketball Queens shirt, in a nearby bar after the game. She was posing for photos with chipper Fever fans while her sister and best friend waited for her at the door. “I’m obsessed with all three,” Thomas, who’d come all the way from Connecticut, said. “They tell me that means you’re not a true fan. But I’m just excited about the attention the league is getting.”

Can this level of fervor last? I imagine for the new crop of fans, it’ll sharpen as they either cohere around allegiances or naturally drift away. For the hot-take economy, it’s hard to say.

“A lot of reporters, they’re here for the moment, not for the movement,” the Sky’s Turner told me before the game. “They tune in when it’s the trending names. You got Caitlin Clark, Angel Reese, it’s huge. Are they going to cover any more games this summer or anything else? I think it’d be cool if people stuck around.”

In Los Angeles last month, the fans did. After the final buzzer sounded, so few people headed for the exits that I wondered for a moment if the newly faithful were actually so green that they didn’t know there were only four periods to a game. But in fact they were just hanging around to see Clark for as long as they could. They cheered as she headed to the courtside seats and posed for photos with the actors Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis — the very sight of Clark brought their daughter to tears — and they cheered as she slowly made her way to the visitors tunnel, proffering sneakers, jerseys, and posters for her signature. It was like watching a ’90s boy band leave the stage after an encore.

In Indianapolis, as the perfectly satisfied sellout crowd eventually headed for the exits, I heard someone ask a young fan, “Your first game, what did you think?” It was remarkable that this game would serve as their starting point.